As businesses increasingly pivot towards sustainability, cotton tote bags have emerged as a popular choice for eco-conscious branding. Made from a natural and biodegradable fiber, these bags seem an ideal solution to reduce plastic waste. However, the journey of a cotton tote from farm to consumer is fraught with environmental challenges that every business owner must understand. This article delves into the critical aspects that affect cotton tote bags: their environmental impact, the production challenges faced in the industry, their biodegradability and disposal methods, and the essential sustainability considerations when selecting cotton totes over other materials. Comprehensive insight into these topics will empower business owners to make informed decisions that align with both their ethical standards and operational needs.

Weighing the Thread: The Real Environmental Footprint of Cotton Totes in a Sustainable Wardrobe

What looks like a simple switch from disposable bags to a cotton tote hides a larger debate about resource use, farming practices, and longevity.

Cotton totes are often presented as a natural alternative to plastics, but lifecycle impacts from seed to bag to disposal matter for a wardrobe built on lasting value. The story is about how often the bag is used, how it is cared for, and what happens at end of life.

Water use is a major driver. Modern cotton farming can require substantial amounts of water; lifecycle analyses show high liters per kilogram of fiber, translating to thousands of liters for a single tote. This highlights that a seemingly small item can involve real water resources. The implication for consumers is that water embedded in a cotton tote is a tangible factor.

Chemical inputs also matter. Cotton cultivation uses pesticides; organic cotton can reduce inputs but yields are often lower, which may require more land or more time to produce the same fiber. Water use in organic systems varies by climate and farming methods.

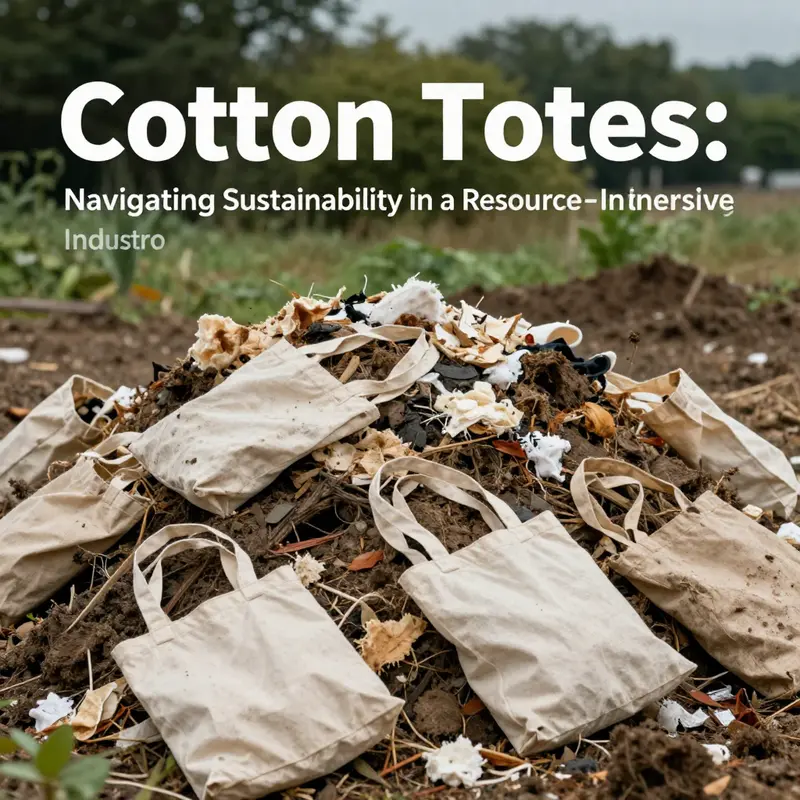

End-of-life matters too. Pure cotton is biodegradable under proper conditions, but this depends on disposal behavior and composting infrastructure. If used many times, the initial production footprint can be spread over many uses. Thresholds for offsetting the higher production costs are found when the bag is reused many times.

Comparisons with recycled materials add context. Recycled polyester or nylon can reduce water and energy in production, but microplastic shedding and end-of-life recycling challenges exist.

Practical guidance: prioritize durability and reuse, care to extend life, and plan for responsible disposal or recycling. Opt for reinforced seams and durable fabrics, and use the bag as a long-term alternative to disposable options. The balance point is not a single attribute but a chain of decisions from farming to consumer use and end-of-life infrastructure. For deeper reading on cotton water use see World Resources Institute analyses and related tote categories focused on durability.

https://www.wri.org/research/cotton-water-footprint

From Fiber to Footprint: Navigating the Production Challenges of Cotton Totes

Cotton tote bags appear, at first glance, as a simple, natural solution to everyday shopping and carrying needs. They promise renewability, biodegradability, and a connection to a slower, more responsible production narrative. Yet the chapter of their story written in fabric and thread is not without its knots. The production challenges surrounding cotton totes reveal a complex ecosystem where sourcing, farming practices, processing, and end-of-life considerations collide with consumer expectations for affordability, durability, and genuine sustainability. To understand what it takes to make a cotton tote that truly earns its eco-credentials, one must look beyond the fiber’s natural appeal and examine the heavy lift required to bring it from field to bag, from seed to seam, and finally to a responsible end of life if and when the bag has outlived its usefulness. This is a field where environmental accounting must be meticulous and lazy assumptions must be avoided, because every tonne of cotton carries a footprint that ripples through water, soil, energy, and land use across continents.

The most persistent obstacle begins with sourcing. Organic cotton, the segment most directly aligned with sustainability claims, remains stubbornly scarce in a world that wants it now and in volumes large enough for mass production. The limited global supply of certified organic cotton translates into higher production costs and longer lead times for brands striving to position themselves as environmentally conscious. The gap between demand and certified supply is not simply a pricing question; it feeds into timing, inventory management, and the ability to scale sustainable lines quickly. In practice, this means that even brands with good intentions may face delays in launching or expanding cotton tote offerings labeled as organic, while mills and farmers navigate contracts, quotas, and the logistics of certified farming practices that can be more labor- and land-intensive than their conventional counterparts.

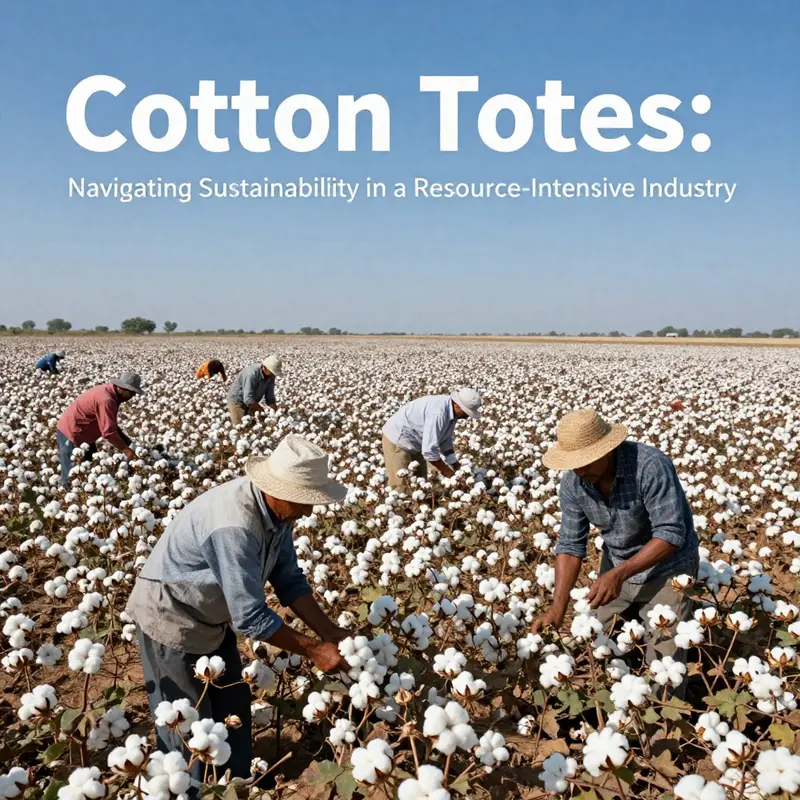

The broader environmental footprint of cotton production compounds these sourcing hurdles. Conventional cotton farming is famously water-intensive, a characteristic that has made it a focal point in global discussions about agricultural sustainability. Estimates often cited in environmental studies indicate that producing a kilogram of cotton can require up to 20,000 liters of water. When translated to a typical tote bag, this figure underscores a stark reality: the water cost of a single cotton bag can be substantial, especially in regions where water scarcity already threatens ecosystems and farming communities. Pesticide and fertilizer use in conventional cotton cultivation further complicates the picture, with potential soil degradation and harm to non-target species, including pollinators and biodiversity that many brands claim to protect through more sustainable product lines. Even organic cotton, while avoiding synthetic chemicals, does not escape the water and land toll. Organic farming often relies on irrigation in arid or semi-arid climates, demanding significant arable land and continuous water input. In practice, this means that the environmental advantage offered by the absence of pesticides must be weighed against other resource expenditures, particularly in areas where rainfall is insufficient to sustain year-round harvests.

A stark illustration of the trade-offs comes from comparative life-cycle analysis conducted by researchers who examined the end-to-end impact of cotton totes. A frequently cited assessment points to a striking threshold: a single-use comparison against certain plastic alternatives, in terms of global warming potential per use, can tilt the scales toward plastics if cotton bags are not reused enough times. A 2017 study by a prominent European environmental agency concluded that an organic cotton tote would need to be reused hundreds or thousands of times to offset the higher greenhouse gas emissions tied to its production when compared with reusable plastic bags. While this kind of finding might be framed as a cautionary note, it is more accurately a call to action for smarter design, longer lifespans, and responsible consumer behavior. After all, the true sustainability of a cotton tote rests not only on how it is produced but how many times it is used and how well it is cared for.

Even when organic cotton is available and used as a responsibly sourced option, trade-offs persist. Cotton’s biodegradability at the end of life remains its most publicized advantage over synthetic materials. A cotton tote, when disposed of properly, breaks down more readily in composting environments and does not persist for centuries in landfills. But this benefit hinges on disposal behavior. If a bag ends up in ordinary waste rather than a compost stream, or if it is discarded after only a few uses, the initial environmental cost does not get amortized in the way its designers envisioned. In contrast, alternatives made from recycled polyester or recycled nylon—materials drawn from post-consumer waste—offer a different kind of ecological calculus. They typically require less water and land during production and can be engineered for long-term durability. Yet they bring their own environmental questions, including the potential release of microplastics during washing and a dependency on non-renewable fossil feedstocks. Cotton totes thus sit at a crossroad where material advantages intersect with practical constraints and consumer behavior grows more decisive with every purchase.

Durability and lifespan emerge as central determinants of true sustainability. A cotton tote that lasts for years and is used repeatedly can significantly reduce its per-use environmental footprint, but achieving this level of durability demands careful design and robust manufacturing practices. The stitching must endure repeated load-bearing use, the fabric must resist abrasion, and the bag’s components—handles, seams, liners, and closures—must withstand the tests of daily wear. These manufacturing choices are not cosmetic. They have real implications for water and energy use during production, the quality of the finished product, and the bag’s ability to persist across seasons and shopping cycles. If a bag wears out quickly and is replaced often, the eco-advantage of the cotton fiber dissolves into a higher cumulative impact than a more durable alternative. In this light, the pursuit of durability becomes a core sustainability instrument: it is the mechanism by which a product can deliver genuine environmental dividends beyond the romance of a natural material.

The industry also faces integration challenges across its value chain. Sourcing organic cotton is only part of the battle; the rest involves the environmental costs embedded in spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing. Each stage demands energy and water, consumes inputs, and can generate waste streams that require proper treatment. Dyeing, in particular, has long been identified as a hotspot for environmental risk when wastewater is not responsibly managed. Even with organic cotton, the finishing processes necessary to produce a bag that holds color securely and wears well over time can introduce additional chemical loads and energy use. The reality is that sustainable branding for cotton totes often hinges on how well a company can optimize each stage of production, from crop selection and irrigation techniques to energy-efficient mills and responsible effluent treatment.

The conversation around cotton totes would be incomplete without acknowledging the market dynamics that shape these production choices. A fair, transparent supply chain becomes as important as the raw material itself. Certification schemes, traceability, and farm-level practices all influence the final product’s credibility. The demand for organic and eco-labeled goods continues to push brands toward higher standards, even as supply constraints test their ability to deliver. In this context, the industry is experimenting with hybrid approaches: using organic cotton where supply is feasible, while deploying recycled materials where the ecological calculus is clearer or where durability and scalability are better aligned with consumer needs. The balancing act is delicate. It requires brands to articulate credible sustainability narratives, manage cost pressures, and invest in long-term capital that can shift the industry’s trajectory away from the most resource-intensive options.

As readers reflect on these production realities, it is worth considering the consumer’s role in shaping outcomes. The difference between a cotton tote that harms the environment and one that truly serves as a lower-impact option rests on usage frequency and care. Reuse, repair, and proper washing practices extend a bag’s life and help to amortize the initial footprint. For those exploring the broader family of fabric totes, there is a continuum of options that blends practicality with responsibility. For readers curious about variations in construction and style that stay aligned with a fabric-first ethos, consider exploring resources that focus on durable fabric tote designs. Fabric tote bags for women can provide a window into how thoughtful construction, robust stitching, and reinforced handles contribute to longevity. This kind of exploration underscores a larger point: the best choice is not a one-size-fits-all verdict on material alone, but a decision anchored in how the bag is used, cared for, and recycled at the end of its life.

In the end, the production challenges of cotton totes reveal a narrative of trade-offs and opportunities. The fiber’s natural appeal remains strong, but it is inseparable from the realities of water use, land management, and the energy demanded by modern textile processing. The path to a more sustainable cotton tote is not simply a question of choosing organic over conventional or cotton over plastic. It is a question of how well the industry can optimize the entire lifecycle—from seed to seam to soil after business ends—while maintaining affordability and practicality for everyday users. It is also about honesty in communication: acknowledging that biodegradability at the end of life does not erase the responsibilities carried during production. When brands invest in scalable sustainable practices, and when consumers commit to durable use and proper disposal, cotton totes can contribute to a palette of responsibly designed bags that respect both the planet and the people who cultivate, manufacture, and carry them.

For a broader market context and to explore comparative analyses across the tote category, the Global Tote Bags Market Report offers a comprehensive view of size, share, and trends shaping both cotton-based and alternative-material bags.

End-of-Life Reconsidered: Biodegradability, Disposal, and the Circular Promise of Cotton Totes

Cotton totes carry more than simply a fashion cue or a shopping convenience. They embody a cycle of use and return that must be understood if we are to judge their true environmental merit. In life-cycle terms, the end of a cotton tote’s story matters as much as its start. The fiber’s natural identity offers a potential advantage: when a cotton tote exits the scene, it can join the earth again rather than linger in a landfill for decades. But the ease with which a cotton tote returns to soil is not automatic. It depends on how the bag was made, what it carries, and how it is disposed of at the end of its usable life. The end-of-life equation is not a simple yes-or-no verdict on sustainability; it is a nuanced balance between material biology and human behavior, between design choices and waste-management infrastructure. In this light, biodegradability is not a one-size-fits-all property. It is contingent, specific to the product’s composition and the conditions under which disposal occurs. The core idea is straightforward: pure cotton, left in the right circumstances, will break down over time. But that simplification can obscure practical complexities that shape real-world outcomes for cotton totes across homes, communities, and landscapes. If we accept that premise, the next question becomes how to maximize the practical biodegradability of cotton totes without compromising their performance during daily use. And if biodegradability is real, what must be avoided to keep that end-of-life benefit intact? The guidance is not esoteric. It hinges on keeping the tote free from synthetic coatings, plastic linings, and other non-cotton additives that can stall or alter the natural decomposition process. It also involves understanding the limits of home composting and the role of municipal or industrial composting facilities in handling textile waste. The story of cotton’s end of life is thus a story of proper design, responsible disposal, and the social behavior that makes either path viable. The most important takeaway is that biodegradability, by itself, does not guarantee a low environmental footprint. The bag must be used repeatedly, and it must be disposed of in a manner that aligns with its biology. Otherwise, the composting potential remains unrealized, or worse, it becomes a marginal footnote in a landfill story rather than a meaningful step toward circularity. When a cotton tote is well engineered—free of synthetic coatings, free of integrated plastics, and kept in good condition through regular care—it can fulfill its end-of-life promise by returning to compost in a relatively short time. This is especially true when the bag is designed with end-of-life in mind from the outset, an approach that supports a circular lifecycle rather than a straight-line disposal path. The contrast with synthetic fibers, which may persist for centuries, highlights the real environmental advantage of cotton’s biodegradability. Yet the contrast also reveals the practical caveat: the mere fact that cotton can biodegrade does not absolve the entire supply chain of responsibility. The fertilizer-heavy, water-intensive journey from seed to finished tote has already left footprints on soil, water, and ecosystems. The end-of-life benefit, then, is best realized when the overall lifecycle is managed with care—minimizing waste during production, maximizing durability during use, and ensuring disposal pathways that honor biodegradability when the bag finally exits service. The end-of-life decision is not merely about tossing a tote into a compost pile. It is about aligning design, material purity, and consumer behavior to ensure that the bag’s final transformation is an actual recovery rather than a missed opportunity. In this sense, the 100 percent cotton tote gains its credibility not only by what it is made from, but by how many times it is used and how it is disposed of when its usefulness wanes. A well-used cotton tote can be a low-impact choice, provided its lifecycle remains tightly managed and its disposal follows appropriate composting routes. Conversely, if a tote is discarded after only a few uses or when it carries non-compostable contaminants, the biodegradability advantage is undercut. The environmental arithmetic is simple in concept, yet demanding in practice: the more times a cotton tote is used, the more the initial production footprint is amortized. The longer its life, the more likely it is that its end-of-life advantage will materialize. The more it retains coatings or components that resist natural breakdown, the less likely it is to contribute to a circular system at the end of its life. Consumers play a pivotal role here. They must choose totes that are genuinely cotton, free from PVC linings or other synthetic barriers. They must wash and care for them in ways that preserve fiber integrity, avoiding processes that would necessitate chemical finishes or treatments that persist post-use. They must also commit to proper disposal when the bag has reached the end of its usable life, seeking out composting avenues that accept textile materials rather than simply consigning the bag to general waste. For many households, home composting provides a meaningful route for biodegradable textiles, including cotton totes, when local facilities lack textile-acceptance programs. However, not all home compost setups are equal. Temperature, moisture, core materials, and microbial activity all influence the rate at which cotton degrades. A well-managed compost pile with the right mixture of greens and browns, maintained at suitable temperatures, can accelerate the breakdown process. The presence of synthetic components, such as plastic zippers or metal eyelets, introduces complexities. Those elements may resist biodegradation or require extraction before composting can proceed effectively. The advice is practical: remove non-biodegradable parts before disposal, and select totes that minimize or exclude such components. This aligns with a broader truth about end-of-life management: the biodegradable potential of cotton is strongest when the entire product is designed for compostability. A bag that is 100 percent organic cotton, untreated, and free of coatings provides a clearest path to biodegradation under appropriate conditions. The packaging and dye choices matter as well. Some dyes, even when used with cotton, can complicate composting, potentially releasing metals or other contaminants. Opting for natural, low-impact dyes or uncolored cotton reduces the risk of introducing harmful substances into the compost stream. In the end, the circular argument for cotton totes rests on a simple premise: use long, dispose well, and choose purity in materials. If these conditions are met, cotton totes contribute to a circular system, offering an end-of-life phase that returns nutrients to the soil rather than to a landfill. Yet it is essential to acknowledge that cotton is not a perfect solution in a world of varied waste streams. Organic cotton reduces chemical inputs during cultivation, but it does not circumvent land and water requirements across the entire lifecycle. And while biodegradability offers a potential advantage at disposal, the true sustainability story emerges only when the bag is used hundreds of times and disposed of through pathways that honor its natural fiber. Consumers who seek a balancing act between practicality and responsibility can view cotton totes as an option within a broader palette of possibilities. For those who want a closer look at the kinds of cotton-based or natural-fiber totes that emphasize user comfort and care, a quick exploration of fabric-tote-bags-for-women can be instructive. This internal resource illustrates how design choices intersect with material purity and consumer habits, guiding choices that maximize longevity and end-of-life friendliness. And when the need is to understand broader implications beyond individual bags, it helps to situate cotton within the wider ecosystem of sustainable materials. In a landscape increasingly populated by products designed for durability and recycled content, cotton totes still offer a distinct narrative: one that foregrounds biodegradability as a legitimate end-of-life option, provided that the bag has been produced without synthetic impediments and disposed of in a manner that supports soil health and resource recovery. The wider conversation also invites consideration of how disposal systems can evolve to accept more textile waste in structured, industrial settings. Industrial composting facilities with appropriate temperature and residence times can process textiles more reliably than home setups, ensuring that the biodegradability of cotton translates into real reduction of waste streams. The EPA’s landscape of plastics and waste disposal underscores a critical point: the path from disposal to recovery is not automatic, and it hinges on whether the waste system recognizes and accommodates textile biodegradability as a legitimate route. Understanding this helps buyers and designers alike move beyond simplistic myths about “green” fibers. It invites a disciplined approach to material selection, product design, and end-of-life planning that aligns with real-world waste-management capabilities. To close the loop, a cotton tote that is truly biodegradable must be more than a single-good product. It is part of a longer chain that includes carefully chosen materials, durable use, and a disposal decision that respects the fiber’s biology. When those pieces align, cotton totes demonstrate the circular promise they often promise in theory: a natural fiber moving toward soil, not toward centuries of persistence in a landfill. The practical takeaway is not to abandon cotton. Rather, it is to refine our expectations and our practices—emphasizing reuse, thoughtful design, and informed disposal—so that biodegradability contributes meaningfully to a broader sustainability effort. For curious readers who want to see how materials like cotton fit into a larger system of sustainable goods, exploring the broader conversation around fabric-focused products and end-of-life management can be illuminating. A related route is to consider tote designs that prioritize purity of materials and ease of disposal, and to engage with textile recycling or composting programs where available. In this ongoing conversation about cotton totes, the end-of-life chapter is not a finale but a continuation—one that invites ongoing attention to how we design, use, and finally return our everyday goods to the earth from which they came. External resource: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-plastics/what-happens-when-plastic-waste-disposed

Weighing the Green Ledger: Sustainability Considerations When Choosing Cotton Totes

Cotton totes are often embraced as a simple, natural alternative to plastic, a choice framed by the idea that plant fibers carry fewer environmental burdens than synthetics. But the full story is more nuanced. A tote bag made from cotton carries a complex lifecycle that begins long before it leaves the factory or the shelf. Conventional cotton farming has earned a reputation for high water demands, heavy pesticide reliance, and soil disturbance. Estimates vary by region and farming practices, yet the central fact remains: cultivating cotton at scale demands substantial resources. The figure most often cited in credible assessments reaches into the tens of thousands of liters of water per kilogram of cotton. This is water that must be found, stored, and managed in arid or semi-arid landscapes, where water resources are already stressed. The farming phase also involves chemical inputs that can influence soil health, biodiversity, and downstream water quality. When those chemicals are used at scale, the entire watershed can feel the impact, with soil microbial life and nearby ecosystems paying a price for intensive cultivation. The manufacturing phase compounds the equation. From cotton fiber to finished tote, processes such as spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing consume energy and may release effluents if not properly controlled. The transport of raw cotton from farm to factory—often across continents—adds another layer of emissions. Each leg of the journey contributes to a footprint that is not confined to a single region but is instead distributed across global supply chains. All of this matters because a cotton tote’s environmental impact cannot be understood in isolation from how often the bag is used, how it is cared for, and how long it endures. The biodegradability that many consumers associate with cotton is a real advantage, but it only translates into lower long-term burden if the bag is disposed of responsibly at the end of its life. A cotton tote that has already worn out after a handful of uses and ends up in a landfill is unlikely to offset its production costs. The environmental math shifts meaningfully when we consider reuse. In theory, cotton’s natural fiber offers a clear end-of-life advantage: compostability, or at least a favorable breakdown in appropriate conditions. Yet the practical reality is that the end-of-life benefit depends on whether the bag is actually composted or disposed of properly, a behavior that varies widely with consumer habits and regional waste systems. The base line of sustainability for a cotton tote thus rests on two tightly linked threads: durability and reuse. When a bag is robust enough to withstand hundreds of uses, its per-use environmental cost drops. If it can be washed and maintained with gentle care, its lifetime grows longer, further diluting the initial resource draw. This logic sits at the heart of any credible assessment: the raw material’s footprint is not the final word; it is a piece of a larger performance ledger. Durability, then, becomes the most consequential factor in sustainable fashion care. A tote designed for daily use, kept in good condition, and repaired when needed can outperform cheaper, less resilient alternatives that rot or lose integrity after a few trips. This perspective is echoed by researchers who argue that durability should be a primary criterion when evaluating the sustainability of any reusable item. As Dr. Lena Patel, a sustainable materials researcher, notes, “Durability is the most underrated factor in sustainable fashion. A bag used daily for a decade has a far lower environmental cost per use than ten cheap alternatives.” The implication is lucid: the value of a cotton tote rises not simply with how it is made, but with how long it lasts and how consistently it is used. With that understanding, consumers can adopt a practical framework for decision-making. First, prioritize construction that speaks to longevity. Heavy-duty stitching, reinforced handles, and fabrics that resist abrasion contribute to a longer life. Second, align the design with realistic usage patterns. A bag that is routinely overloaded or treated as a fashion prop may fail prematurely. True sustainability, then, hinges on balancing capacity, durability, and care. Third, cultivate care habits that extend life. Gentle washing in cold water, air drying, and avoiding aggressive chemical detergents help preserve fiber strength and color. Each of these steps reduces the need for replacements and sustains the bag’s utility over time. Given these considerations, the comparison to alternatives becomes clearer. Organic cotton offers reductions in chemical inputs during growing and processing, which mitigates some ecological footprints. Certification schemes such as the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) provide a framework for regenerative farming practices and safer conditions along the supply chain. Even so, organic cotton does not automatically guarantee lower water use or smaller land footprints in every context. The total impact still depends on how the cotton is farmed, how it is processed, and how far the product travels before it reaches consumers. Local sourcing offers another route to reduce transport-related emissions, though it does not always align with the most resource-efficient farming systems. When weighing cotton totes against alternatives such as recycled nylon or recycled polyester, the differences are nuanced but meaningful. Recycling inputs based on post-consumer waste can substantially lower overall resource extraction and land use during production. Engineered for durability, these materials can deliver long service lives with lower water and land footprints during manufacture. They may also offer easier repairability and better performance in challenging conditions, reinforcing the case for longevity as a pathway to sustainability. Yet even here, the ultimate sustainability outcome depends on real-world usage patterns. A well-constructed cotton tote used extensively can outperform a suite of poorly built synthetics replaced frequently. Conversely, a low-cost synthetic bag designed to last only a short period will not perform as well in environmental terms. The practical decision for most consumers, therefore, is not binary: it is a nuanced calculus that weighs material attributes, production practices, and anticipated use. It invites a moment of reflection about where one lives, how water is valued, and what waste systems look like in the local community. If a consumer knows they will use a tote frequently, investing in heavier fabric, stronger seams, and a design that resists wear makes sense. In such cases, the end-of-life advantage of cotton—its biodegradability—can be realized if and when the bag is eventually disposed of in a compostable or properly managed waste stream. But if the turnover is high, and the bag is replaced every season, the overall burden may tilt toward synthetic options engineered for long life and lower production footprints per unit of use. The core message is that sustainability is situational, not universal. It invites a thoughtful forecast of personal habits and local waste realities. In practice, that means asking questions before purchase: How many times will I realistically reuse this bag? How will I wash and care for it? Will I keep it for at least a couple of years, or will it be replaced as fashion shifts? Will I have easy access to a recycling or composting stream for textiles at the end of its life? Answering these questions helps align expectations with outcomes and encourages a more intentional approach to the tote as a resource rather than a disposable item. For readers who want to explore a broader landscape of durable tote options and to compare materials without losing sight of local conditions, there is value in examining alternatives that favor longevity and lower resource extraction. If you’d like to see a representative example of durable, regionally accessible options, you can explore the broader category of canvas totes and related styles here: women’s canvas tote bags. That link offers a sense of how sturdiness and capacity translate into real-world performance, while keeping the focus on items that prioritize long-term use rather than short-term novelty. Ultimately, the best choice remains context-driven. A cotton tote can be a responsible option when it is designed for longevity, used repeatedly, and cared for over many years. It can also be a stepping stone toward a more sustainable wardrobe when selected with attention to farming practices, processing standards, and transport realities. In some environments, especially where water stress is acute and waste infrastructure is robust, organic cotton with strong durability can present a compelling balance of natural material and responsible production. In others, recycled materials with proven lifespans may be the smarter selection, reducing the total burden placed on ecosystems from resource extraction to end-of-life. The question, therefore, is not simply which fiber is best, but how a consumer’s behavior, location, and waste systems shape the true environmental cost of a tote. The science is clear enough to guide those who are willing to look beyond simple keywords like “green” or “natural.” A thoughtful approach blends material knowledge with practical use, care, and end-of-life strategy. For a rigorous, peer-reviewed assessment of this topic, see the detailed life-cycle analysis in the scholarly literature: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095965262500342X

Final thoughts

Choosing cotton tote bags can significantly contribute to a business’s sustainability efforts, provided that the environmental implications and production realities are understood. While cotton has distinct advantages in terms of biodegradability, it is imperative to consider the water consumption and pesticide use during production. As businesses aim to align with eco-friendly practices, evaluating the lifecycle of these products is paramount. Prioritizing reusability and longevity will not only mitigate initial environmental costs but also enhance the brand’s commitment to sustainable practices. Ultimately, it’s essential to consider not just the material but the frequency of use and how well the product is cared for. By fostering a culture of reuse, businesses can turn cotton totes into a truly sustainable option in their operations.